A gross oversimplification of the English common law system is that the law aims to punish evil and protect property. More often than not this gets shunted into the categories of criminal and civil law. In the age of monarchy and feudal obligations, the legal profession was relegated to an even smaller minority of literate people. Often times this minority was composed of clerics from which we get the word “clerk.1” The legal system was extremely formalized and even minor derivations from the prescribed form may result in a case being tossed out. The power of the law was limited in the types of remedies it could provide. To achieve greater fairness or equity, at least since King Edward IV the Crown established the court of Chancery to adjudicate a variety of property cases2.

In England, the Chancellor was a special judge appointed by the Crown to oversee these cases. The Lord chancellor still exists in England to this day. The Chancery courts were different from the “courts of law” in evidentiary requirements, procedure, and most notably the relief they could provide. The Chancery focused almost exclusively on issues of property and contract, thus the remedies are focused on those issues. Equitable remedies included injunctions, specific performance, rescission of contracts, and restitution. For example, if you entered into a contract for the sale of land and a person refused to honor that contract the Chancellor could force the sale. Another example is if a neighbor is repeatedly violating your property by stealing your fruit the court of Chancery could issue an injunction on the neighbor. If the neighbor violated that injunction they could be subject to punishments for contempt of court.

In the United States, the courts of Chancery became fused together with courts of law. Thus, if an individual is seeking both monetary damages, which is a function of law, and an injunction, which is a function of equity, they can achieve both in a single court. A notable exception is that the US still has bankruptcy courts which were traditionally an issue of equity. An even more notable exception is Delaware which still has courts of Chancery. This is part of why so many businesses are incorporated there.

In the late 19th Century with the rise of capitalism, an investor seeking to profit off a venture would purchase a portion of a company. These cumulative shares comprise an individual’s equity in the company. Equity in this instance means the ownership of the company. In bankruptcy, the remaining assets are distributed to those who have equity.

As you can probably imagine this is a very very simplified version of the history of equity. However, I think the key points to remember are that (1) Courts of law and equity were separate. (2) Courts of equity called the Chancery focused on providing a set of remedies relating to property and contracts. (3) Issues of equity are functionally different from law even if today they may be adjudicated in a court of law.

Next time we will look at definitions of equity as it is presently used and distinguish it from its historical and etymological roots.

1. Oxford, The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology 181 (C.T. Onions, 1966)

Back to text.

2. Thomas A. Robers, Esq., The Principles of the High Court of Chancery, and The Powers and Duties of Its Judges; Designed as The Student’s First Book on Equity Jurisprudence 5 (Wildly and Sons, 1852).

For the remainder of this post, you can assume I am getting my information from this book. If you wish to read it yourself there is a free copy available here.

Back to text.

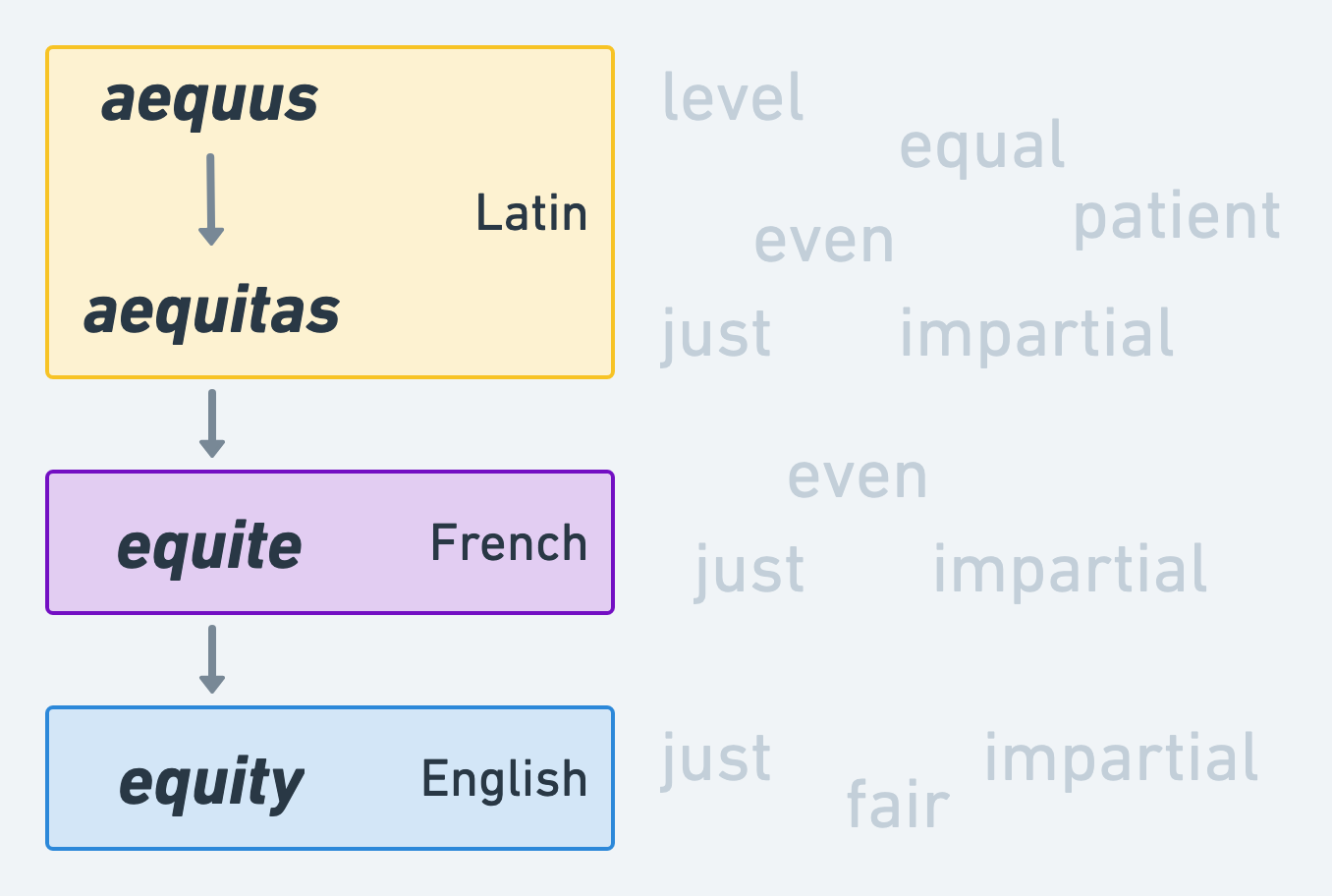

The word equity (n.), like most of our legal words, comes to us from Latin through Old French. The Latin term aequitas (n. f. nom. sing.) entered Old French and became equite which over the march of history eventually became the English equity.

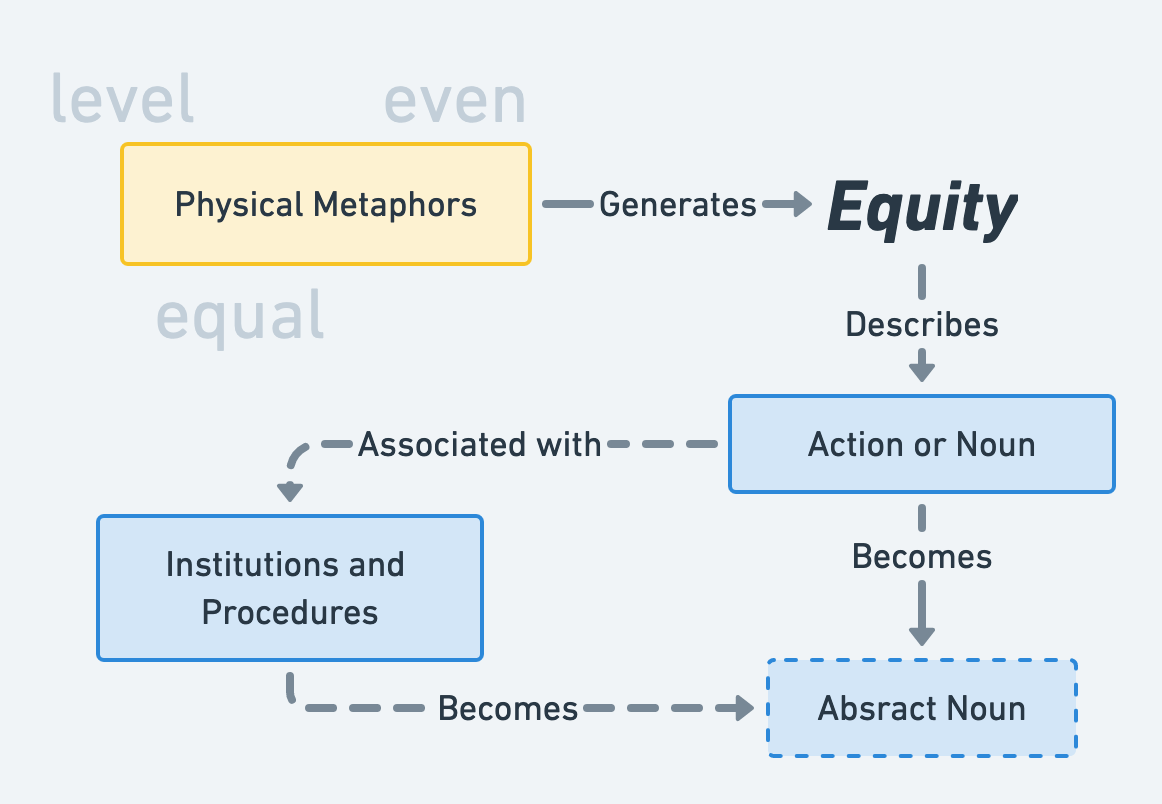

The word equity (n.), like most of our legal words, comes to us from Latin through Old French. The Latin term aequitas (n. f. nom. sing.) entered Old French and became equite which over the march of history eventually became the English equity. Second, even when we use the term as an adjective or adverb, the word is rooted in physical metaphor. The most tangible is the metaphor of even ground. This is conceptually related to the idea of similarity. The ground is level when it is uniform or similar. By abstraction, we think of a game as equitable when it is on a “level playing field.” When there is no slant towards one side. As a bizarre coincidence, the term inequitable has its origin in the Latin word inequabilis which is rooted in the similar-sounding term equus which means “horse.” For the ground to be inequitable also meant it was impassable for a horse

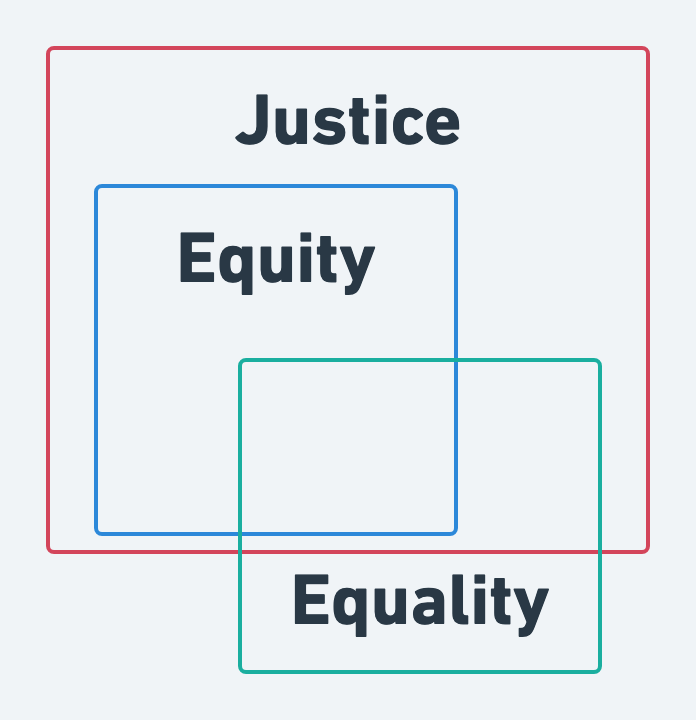

Second, even when we use the term as an adjective or adverb, the word is rooted in physical metaphor. The most tangible is the metaphor of even ground. This is conceptually related to the idea of similarity. The ground is level when it is uniform or similar. By abstraction, we think of a game as equitable when it is on a “level playing field.” When there is no slant towards one side. As a bizarre coincidence, the term inequitable has its origin in the Latin word inequabilis which is rooted in the similar-sounding term equus which means “horse.” For the ground to be inequitable also meant it was impassable for a horse Third, equity is related, both conceptually and grammatically, to equality. Likewise, they are conceptually related and similar in grammatical function to the term justice. However, they are also distinct. As we explore the history of equity more fully we will see how to distinguish these concepts and terms more precisely. Initially, it is worth noting justice is more extensive and contains equity, while equality overlaps the two while not being contained by either

Third, equity is related, both conceptually and grammatically, to equality. Likewise, they are conceptually related and similar in grammatical function to the term justice. However, they are also distinct. As we explore the history of equity more fully we will see how to distinguish these concepts and terms more precisely. Initially, it is worth noting justice is more extensive and contains equity, while equality overlaps the two while not being contained by either

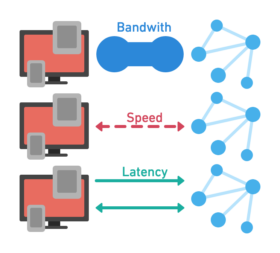

For your everyday consumer, a low latency highly reliable mesh network means the advent of augmented reality devices. At the moment, a major hurdle of augmented devices is the data processing of input data from sensors. If the local device needs to compute that data it adds substantial physical weight in order to provide sufficient computing power. Whereas if the device is integrated into a wireless network all it needs to do is send data, receive the processed data, and display the results. Meaning you could wear a light pair of glasses equipped to record your surroundings and display real-time information.

For your everyday consumer, a low latency highly reliable mesh network means the advent of augmented reality devices. At the moment, a major hurdle of augmented devices is the data processing of input data from sensors. If the local device needs to compute that data it adds substantial physical weight in order to provide sufficient computing power. Whereas if the device is integrated into a wireless network all it needs to do is send data, receive the processed data, and display the results. Meaning you could wear a light pair of glasses equipped to record your surroundings and display real-time information. As one might expect 5G technology is complicated. It should not come as a shock the legal dynamics are also complicated. Those legal issues were the focus of the

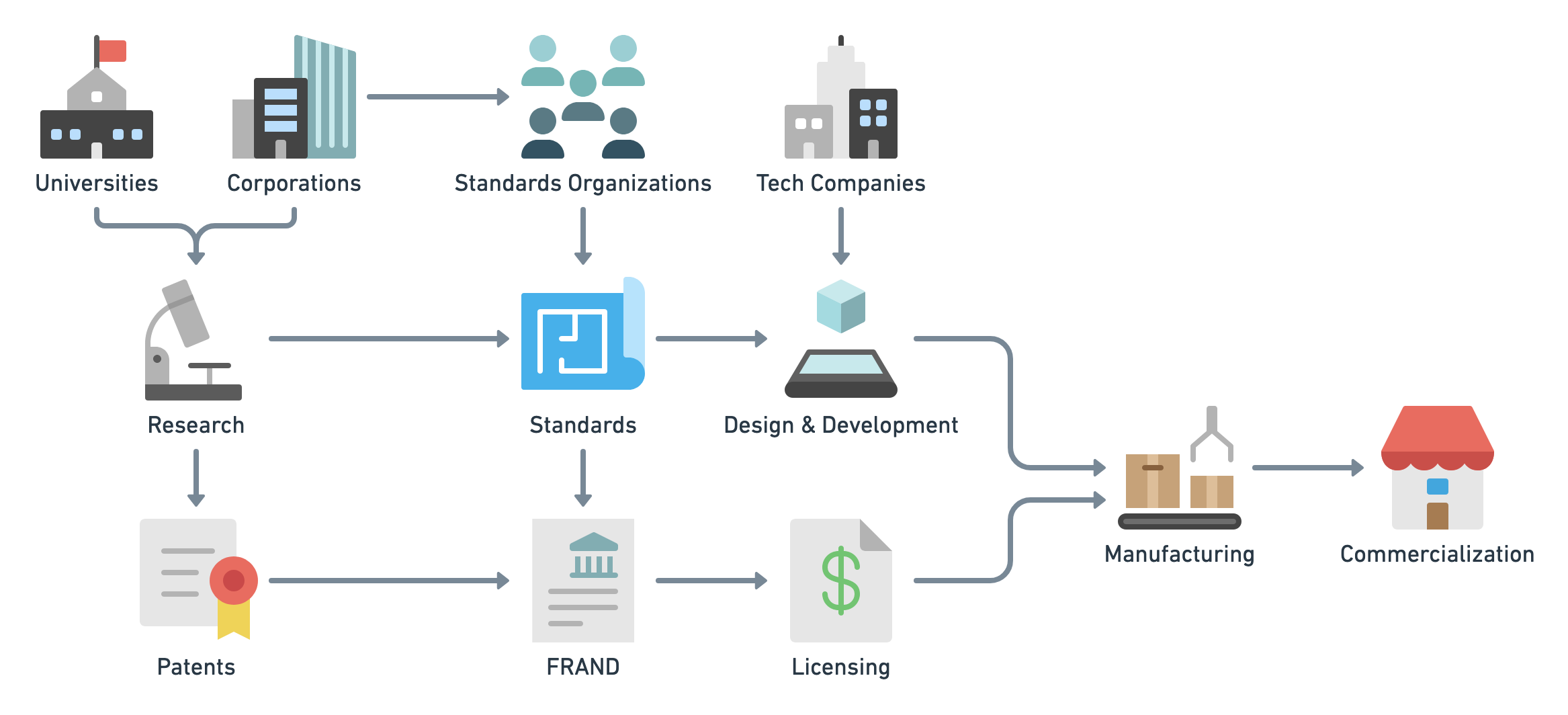

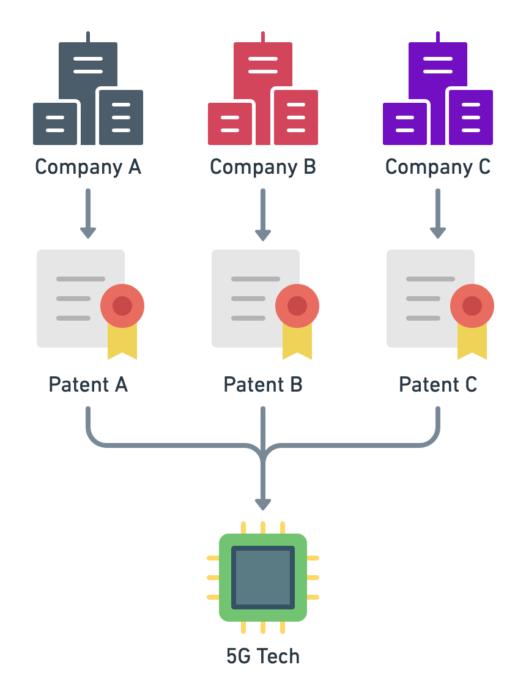

As one might expect 5G technology is complicated. It should not come as a shock the legal dynamics are also complicated. Those legal issues were the focus of the  These various companies who develop 5G technology come together to oversee standards in organizations, such as the International Telecommunications Union and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. The standards organizations set technical standards enabling the various technologies to work together. The standards are like a building code. From there the inventors and producers of devices can build the specific devices and physical tech.

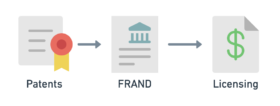

These various companies who develop 5G technology come together to oversee standards in organizations, such as the International Telecommunications Union and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. The standards organizations set technical standards enabling the various technologies to work together. The standards are like a building code. From there the inventors and producers of devices can build the specific devices and physical tech.  As part of the standardization agreement, these companies who hold these patents agree to Fair Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory licensing agreements (FRANDs). In theory, this should make it easier for manufacturers to license from the patent holders. Unfortunately, that is rarely the case. Smaller manufacturers, in particular, have a significant disadvantage in determining who to license from and negotiating a reasonable rate that will actually be accepted by the market.

As part of the standardization agreement, these companies who hold these patents agree to Fair Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory licensing agreements (FRANDs). In theory, this should make it easier for manufacturers to license from the patent holders. Unfortunately, that is rarely the case. Smaller manufacturers, in particular, have a significant disadvantage in determining who to license from and negotiating a reasonable rate that will actually be accepted by the market.